This is my first blog from my holiday reading. Two weeks just South of Barcelona and I know that experience of sun, sight-seeing and family time makes me one of the ‘lucky’ ones. This has been my second jaunt abroad this year, something well out of the reach of many others. An important aspect of a holiday is that it affords me time to read and therefore to consider The Lives of Others. Mukherjee’s title could hardly be more apt for the study of social work and social policy and yet what happens if my reading is so far removed from my experience, can I still really claim to have gained an understanding of the ‘other’?

This is my first blog from my holiday reading. Two weeks just South of Barcelona and I know that experience of sun, sight-seeing and family time makes me one of the ‘lucky’ ones. This has been my second jaunt abroad this year, something well out of the reach of many others. An important aspect of a holiday is that it affords me time to read and therefore to consider The Lives of Others. Mukherjee’s title could hardly be more apt for the study of social work and social policy and yet what happens if my reading is so far removed from my experience, can I still really claim to have gained an understanding of the ‘other’?

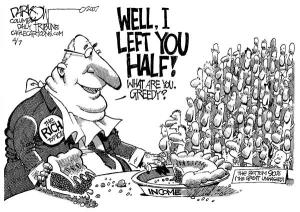

This is a novel about inequality. This is something that social policy can tell me a great deal about, especially from a UK perspective. According to the UN Development Report in 2013 (Find report here) inequality in the UK has risen sharply since 1991 and warns that this inequality is exacerbated by economic policy which “may well worsen the prospects for recovery and growth” (p22) and impact on future generations. As inequality has risen, intergenerational mobility has declined (p36).

However, despite knowing this and despite understanding that many families in the UK are using debt to secure necessities (See guardian article here ) and that my local Tescos has a food bank collection, it can still be difficult to think of the UK as struggling. As Mary O’Hara (2015: 2) points out in her brilliant book Austerity Bites:

“Even when the country was in the midst of a recessionary slump of historical proprotions it wouldn’t have been difficult to find a place where people appeared to be doing okay.”

This is true when viewed from the heights of academia. It must be even more true from the dizzying heights of the millionaires in the cabinet (See Daily Mirror article here ). Therefore, it would have been so easy to turn away or to dismiss The Lives of Others from its prologue which details the poverty, squalor, desperation and hunger of the last hours of Nitai Das in 1966 somewhere in West Bengal. It is so far from what I know, I could read it as mere, grotesque spectacle or the current term, “Poverty Porn” (Good blog on the concept of poverty porn from JRF here ).

But I don’t because the writing is so deeply affecting, I have to keep considering the lives of others and what I can know and understand of them. As Supratik, a significant character of the novel and an active member of India’s Communist Party, notes in his diary (pp177 – 8):

“Sometimes, I use a different approach, I concentrate on one probable experience in his life and try to become him and live that experience in every single sensation and feeling… I open my eyes. The centre of my head feels heated. And yet I’m no closer to that man. Most importantly, I haven’t been able to answer that big question, what idea did he have of the story of his life, not only of the past and the present, but also of what was to come?”

This is a discussion about the limits of empathy and as Pogge (2007: 143) notes:

“Wealth affects people’s perceptions and sentiments, makes them much less sensitive to the indignities of poverty and much more likely to misperceive their own wealth as being richly deserved and in the national interest”

In other words, it is harder to see, acknowledge and feel others struggles from a position of privilege, both internationally and when looking at your near neighbour. Yet, as this novel explores, our lives are only worth living because we live with, for and alongside others. When we neglect the ‘other’, we neglect our humanity and inequality is particularly corrosive to that humanity. The novel, however, does not present a straightforward account of how other people provide for and support our humanity. It shows us the challenge of gossip:

“She raised her voice as she progressed through her litany, the escalation in volume and the accusations feeding off each other. Within minutes a small crowd had gathered: what could be more interesting than other people’s lives?” (p330).

It details the problems of closed communities:

“This is how the world runs, a small group of people who know each other, a closed world of intense curiosity in other people’s lives because your own is just empty, dead time” (p390)

It considers how we story past lives and events to both shed light on and diffuse the current life:

“The anecdotes need not be first-hand; in fact, better if they are not, better if they are repeated across several degrees of separation, because that proves how potent and pervasive they are, bringing everyone together in one huge collusive matrix… Chatter, chatter, chatter, always the chatter of what others did and others said in a golden age of an unrecoverable past” (p394).

Furthermore, it shows that political ideology is no replacement for understanding:

“But his mother dents his carapace. Watching, when he can bear to the three-way pull between relief, fear and curiosity on her readable face, her fear barely winning out over her indestructible love, something goes through the rickety cage of his chest, but he stops it there. Emotion is a luxury, he knows; like all revolutionaries he cannot draw the correct line between emotion and sentimentality” (p419).

What the writer does so well, is allow us to see that there are other ways to see the story which do not mean that empathy is lost or diluted. Amidst the beauty of the country and the writing, the author does not disguise or excuse the disorder of society.

I’ve recently written about a Utopian vision in Woman on the Edge of Time (Piercy, 1976). Mukherjee’s portrayal of this real and socially-constructed dystopia explain the brutal attempts to change it, but also acknowledges that it cannot stay the same.

I’ve recently written about a Utopian vision in Woman on the Edge of Time (Piercy, 1976). Mukherjee’s portrayal of this real and socially-constructed dystopia explain the brutal attempts to change it, but also acknowledges that it cannot stay the same.

“For those who still think that utopia is about the impossible, what really is impossible is to carry on as we are, with social and economic systems that enrich a few but destroy the environment and impoverish most of the world’s population. Our very survival depends on finding another way of living” (Levitas, 2013: xii).

For me, the role of social policy is not just to document the social realities, but also to consider and to act on the future possibilities of the lives of others.

References

Levitas, R. (2013) Utopia as Method: The Imaginary Reconstitution of Society Hampshire: Palgrave

Mukherjee, N. (2014) The Lives of Others London: Vintage Books

O’Hara, M. (2015) Austerity Bites Bristol: Policy Press

Piercy, M. (1976, 1988 reprint) Woman on the Edge of TimeLondon: The Women’s Press

Pogge, T. W. “Why Inequality Matters” in D. Held and A. Kaya (eds.) Global Inequality: Patterns and Explanations Cambridge: Polity Press